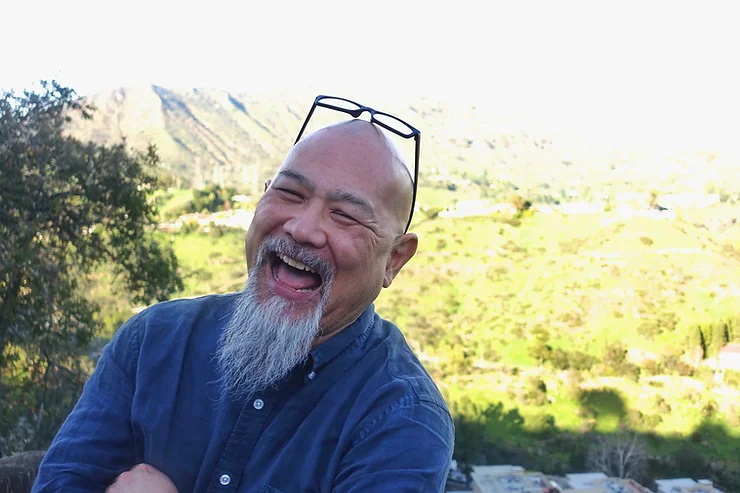

With the upswing in Asian-American representation in cinema in recent years, Caylee So’s The Harvest marks another notable achievement in this vein. Doua Moua (Gran Torino, Mulan) pulls double duties here as screenwriter and leading man as the protagonist Thai, who returns home to help out his family. They are struggling in the wake of patriarch Cher’s (Perry Yung) recovery from a car accident and his kidney failure. Rifts and divides soon develop within the family unit, between father and son, and extending to Thai’s mother Youa (Dawn Ying Yuen) and his sister Sue (Chrisna Chhor).

In many ways, this is the kind of story audiences have seen many times before. The generational divide between the younger and older generations, the grappling with secrets and disappointments, the tensions and eventual resolutions — they are all familiar territory. But in its often vibrant portrait of the Hmong community and traditions, and the eloquent articulation of the nuances beneath the surface, something more distinct is gradually revealed over the course of the narrative.

So’s understated direction is a notable asset here, playing many of the emotions of the film close to the chest. She deftly knows when to let a scene breathe, the camera letting us settle into its wavelengths. From a casual barbeque outing to a Hmong wedding ceremony, she directs in a way where viewers get a sense of the community and environment, establishing details about characters in an unfussy yet distinct fashion.

There’s the occasional more melodramatic beats that don’t work, but on the whole it maintains a nice, low-key tone, capturing a real lived-in sense of this Hmong community. This can be credited to both Moua and So having an authentic first-hand experience of the culture. There is never an outsider’s perspective, or the sense of these characters being mere representations of themes and tropes. These characters represent broader truths but also specific, complicated dynamics that make them feel authentic.

While still well-written, the screenplay could’ve done with adding more detail to some of its character dynamics. The father-son relationship is deftly explored, and the siblings’ interactions are filled with a real authentic quality; on the other hand, some of Thai’s relationships with the neighbouring community feel a bit extraneous, and I would have loved to have spent more time with the mother and her internal life, which feels slightly underserved by the narrative. It’s a testament to Yuen’s terrific performance, which conveys so much in her silences, that this doesn’t feel too detrimental, and it speaks to the strength of the film that the more time we spend with its characters, the more vivid and real they feel.

A potential challenge for the viewer could come in the form of Thai, with Moua giving a rather understated and arguably detached performance in the leading role. This serves its purpose well as a character coming home more out of dutiful obligation than fondness, and there’s enough variation over the course of the film, as we see his secrets and anxieties come out, that propel the film forward.

The central conflicts of the film revolve around Cher and Yung’s performance, and the way in which even in his ailing state, the patriarchal figure wields an iron fist over the household even as he struggles to take care of himself. The film wisely keeps a constant critical eye over Cher’s less savoury qualities as his bigotry and entitlement over governing the lives of his children are met with the right sort of pushback from other characters. Yung’s performance is key to this as he plays into the prickly, often unlikable qualities of Cher while always humanising the character, making sure we see him as not some cipher or straw man, but a deeply flawed, human character.

The film excels most at its eruptions of the frayed family bonds, where it moves into its most deeply specific moments. The struggle of the generational divide to reconcile with one another, thankfully, feels honest and sincere as written, directed, and performed, where beneath the arguments there is always the capacity for progress and moving on as the story threads come together in a heartfelt fashion.

The final act of the film is built upon many revelations, and while some work better than others, the overall achievement is one that strikes the right balance between realism and catharsis. Diaspora films about returning home and coming to terms with the past and present can occasionally feel a bit vague, but thankfully The Harvest, while hitting some familiar beats, feels honest and specific enough in its observations to be considered a fine example of its ilk.