As the condensed version of the story goes, Chinese-American filmmaker Alice Wu was working at Microsoft when she began writing the story for her directorial debut, Saving Face. She first conceived the idea as a novel, but eventually pivoted towards film. She later enrolled in a screenwriting class, quit her job, and moved to New York to get her film made. A handful of years later, Saving Face made its premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival in 2004.

Saving Face wasn’t exactly a box office juggernaut, but its impact, particularly on queer, Asian, and queer Asian audiences, was immediate. In fact, the film is still screened, studied, and celebrated to this day. At present, it remains one of the few lesbian movies in American film history to not only feature Asian women in the lead roles, but also have a happy ending.

Following Saving Face’s critical reception, however, Wu seemingly retired from the industry to take care of her ailing mother. It wasn’t until the late-2010s that she started writing a new script, which would ultimately become 2020’s The Half of It, her sophomore directorial feature.

As of this writing, Wu has no reported films in the works, and these two films remain her only feature-length credits as a director. However, this is precisely what makes Saving Face and The Half of It fascinating to study as a pair of films in dialogue with each other: more than just an excellent—and highly recommended—Alice Wu double feature, there’s a cinematic sisterhood in the way they both explore queerness through the perspectives of their Asian-American lesbian protagonists. Specifically, Wu positions shame and desire as two sides of the same queer coin, one always at war with the other in an effort to end up on top.

In Saving Face, Michelle Krusiec plays Wilhelmina “Wil” Pang, a Chinese-American surgeon who unexpectedly finds herself taking in her 48-year-old widowed mother, Hwei-Lan (Joan Chen), after she is shunned by her own parents and community as a result of an unexpected pregnancy. This comes at the worst possible time for Wil, of course, whose secret relationship with Vivian (Lynn Chen) has just turned serious.

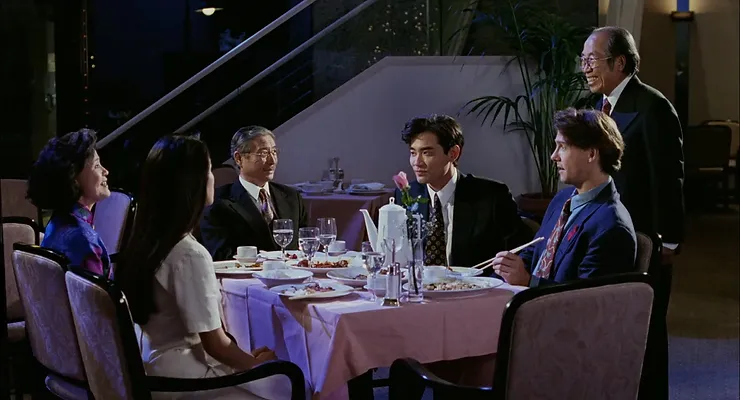

For better and worse, tradition dictates truth for the film’s characters; rules and customs are foremost meant to be followed—which is something Wu wastes no time in establishing. At the beginning, for instance, Wil is dragged by her mother to a large gathering in a local restaurant that effectively serves as a modern mating ground for elder members of their (Chinese) community to introduce their sons and daughters as potential marital matches.

Everything you need to know about the stakes in Saving Face is found here: how the community gossips about each other; how, as a result, you must present yourself in a way that’s deemed appropriate and acceptable; how important it is to honour your parents’ wishes; and how, otherwise, your actions can reflect poorly upon your family. There’s very little leeway for individuality, in other words, which is further emphasized by the isolationist way in which the camera shoots most of the characters in this scene (either alone or in familial units), as if boxing them into their respective frames and, thus, roles within the community.

Wil herself plays the part of dutiful daughter well in this scene, placating her mother’s efforts to set her up with eligible bachelors, politely dancing and engaging in conversation with them while at the party. Elsewhere in her life, she has even achieved the prototypical dream many Asian immigrant parents set for their Western-raised children by becoming a surgeon who, on top of it all, is on track to become the youngest Chief of Surgery ever at her hospital.

And yet, Wil lives a deeply closeted life, not really allowing herself to date women, at least publicly. In fact, although Vivian outwardly flirts with her and makes her romantic intentions unambiguous, Wil scurries away, hesitant to pursue. And even after their romance does begin in earnest, it’s mostly in the privacy of Vivian’s apartment.

There is indeed a quiet shame Wil feels about her queerness that is most timely when you consider the context in which Wu was originally writing Saving Face. The vocabulary and iconography for queer folks today weren’t as nearly extensive, accessible, or, for that matter, mainstream as they were in early-2000s America. What’s more, when you intersect the American sociopolitical ideals of this time with the traditional Chinese values put forth by Wil’s family and community, what you’re left with is two governing cultural bodies telling her the same thing: being gay is not just wrong, but also an impossibility when it comes to being part of the family.

The handful of times we do see Wil and Vivian out in the world together, they’re at a kids playground, far from spying eyes, never standing too closely, and are almost always shot behind or between the metallic structure of the jungle gym. They are together, but always separated by beams and bars—a veritable prison.

These ideas of tradition and familial obligation tread similarly in The Half of It. The film stars Leah Lewis as Ellie Chu, a high school student who keeps to herself in her small fictional hometown of Squahamish, Washington. She has resigned herself to a quiet life, until Paul (Daniel Diemer), one of the jocks, hires her to write his love letters to Aster (Alexxis Lemire), a classmate, for him. What Paul doesn’t know is that Ellie also harbours a secret crush on Aster. Though she initially agrees to Paul’s request solely for financial compensation, what Ellie doesn’t expect is for Aster to write back or, more surprisingly, that they would genuinely connect with each other over a shared love of art and philosophy.

More than just cultural echoes, there are striking parallels between the protagonists of Wu’s films as well. Like Wil, Ellie is fiercely intelligent; she is an exceptional student, whose writing shows immense promise. Her English teacher even encourages her to apply to a renowned liberal arts college in the Midwest. However, Ellie declines—rather persistently if also painstakingly—choosing instead to stay with and support her father, who has fallen into a deep depression since her mother died.

In terms of romance, there are little to no prospects for Ellie. Squahamish is a small enough town that everyone knows everyone else, and religious enough that they all gather at service every Sunday (during which Ellie herself participates as the organist). Of course, the residents are also charming enough that you would be forgiven for thinking they might not hold conservative values, but when Paul discovers Ellie’s feelings for Aster—whose father, as the cherry on this sundae, is the church’s pastor—he tells her that she’s going to hell.

Evidently, for Ellie, shame lives on two fronts: there’s the classic shame churned by implicit (and later explicit) homophobia from the church-going community she lives in, and there’s the somewhat self-inflicted shame attached to her deepest desire to leave Squahamish and realize her full potential, which would effectively mean abandoning her father, who has already suffered a profound loss. In each case, she forgoes what she wants in order to do what she believes will please or is best for the other(s).

Ellie’s bicycle, here, is an apt visual motif Wu returns to again and again. Solitary and linear, throughout the film, we see her constantly biking between the town, where school, church, and community are, and the train station, where her dad and home are. It’s a monotonous, though gruelling, commute, and Wu’s camera never wavers in showing us just how taxing it is on Ellie—and, more than anything, how she just accepts it. Indeed, there’s a certain dignity, however heartbreaking, to the way she, without outward bitterness, never tempts questions about her place in the community and in her household.

All this said, what’s most interesting about Wu’s pair of films isn’t only how they mirror each other on spiritual, cultural, and narrative levels, but also how they each capture the intricacies of shame and desire in two different moments in time—both experiences similar yet different—two bookends of a milestone period in history of queer revolution and, in fact, revelation.

The Half of It takes place (and was released) almost two decades after Saving Face, which is not an insignificant amount of time, especially when one considers the proliferation of queer cinema, discourse, and activism—on a mainstream and global stage, too—during these years. By the time The Half of It landed on Netflix, it was far from the first or only queer movie available to stream. Indeed, queerness—in life, in body, in cinema—was no longer relegated to the shadows of niche and anonymity as it might have felt during the time of Saving Face. Now, in 2020 and beyond, we can see as vibrant a rainbow as it’s ever felt.

This isn’t to say homophobia, bigotry, or notions of shame from the time of Saving Face are completely non-existent now—of course, it still burns in many places and communities—nor is this meant to imply that queer joy was unattainable in any context but the contemporary one seen in The Half of It. What can’t be denied, however, is the crescendo of progress that happened between the two films, on-screen and off.

Which points to what Wu might have known all along: when wrestling with shame and desire, art is the key to liberation. In Saving Face, Vivian is the personification of this. Classically trained in ballet, but wanting to break free to pursue modern dance, she lives in her body in a way that is certainly enticing to Wil, but also profoundly inspirational. Similarly, in The Half of It, Aster is an artist with whom Ellie can finally bond over a shared love of classic literature, art history, and cinema during its golden age. By the end, both she and Aster make their respective decisions to pursue their artistic passions and ultimately live their own lives as they’d always imagined.

In the pantheon of queer cinema, there will forever exist a special place for Wu’s films. It may sound hyperbolic to say so, but there’s a singularity to her career—and, by extension, her legacy—that is unmatched. With just two movies, she reminds us that to live is to love, to be in pain, and, most of all, to create.