Seagrass is an FIPRESCI Prize-winning family drama by writer and director Meredith Hama-Brown. In her debut feature, Hama-Brown mines some elements of her own identity, crafting a story about a Japanese-Canadian woman in an interracial marriage who grapples with grief and generational trauma at a picturesque British Columbia family retreat. The film stars Ally Maki as Judith, Luke Roberts as her husband Steve, Nyha Huang Breitkreuz as their older daughter Stephanie, and Remy Marthaller as their younger daughter Emmy.

At the start of Seagrass, Judith has brought her family to a vacation site by the West Coast to engage in couples therapy after the recent death of her mother. Stricken by a heavy sadness that puzzles Steve and feeling on edge all the time, Judith grieves by bringing along a handmade knit blanket from her mother’s house, which she sleeps with every night. She is eager to find answers in group counselling, while Steve is more standoffish, not quite engaging full-heartedly but not outright rolling his eyes at what he perceives as meaningless emotional performativity.

The two end up interacting with another interracial couple attending the sessions: young, childless, and attractive Pat (Chris Pang) and Carol (Sarah Gadon), who are also Asian and white, respectively. Judith is drawn towards the far more emotionally open Pat, who can relate easily to her Asianness, which is something that Judith has been uncomfortable sharing with her husband. Steve, however, becomes irritated by Pat’s perfect life, expensive car, and closeness to Judith. Pat and Carol’s healthy marriage holds a mirror up (literally) to Judith and Steve’s, making Judith question her relationship more and more.

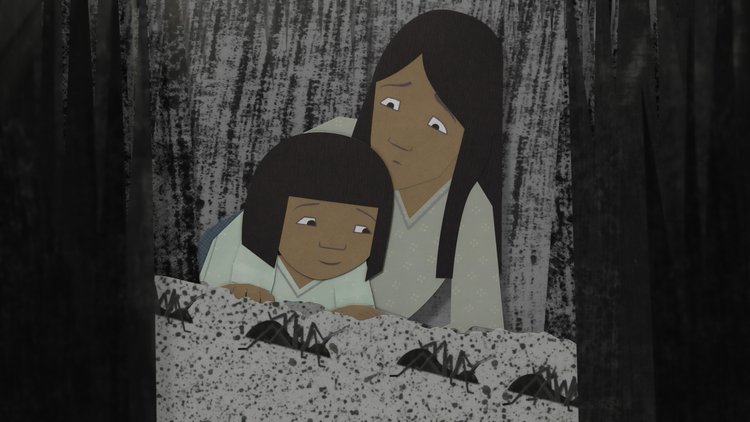

Meanwhile, Judith and Steve’s young daughters attempt to socialize with the other children at the retreat, who are primarily rambunctious white children who tease and even bully the biracial girls. Stephanie finds a way in with the meanest of the “cool” girls while shy Emmy is left feeling abandoned by her big sister. The sisters’ shifting relationship is deeply explored as they are caught between the gaze of callous outsiders and the unspoken tension between their parents. The film is able to take on the perspectives of all three female leads as they navigate the changing dynamics within the family and with their new vacation “friends.”

Maki turns in a great performance as the simmering Judith, but the real casting gold is in the two youngest leads. Huang Breitkreuz and Marthaller clearly have a strong rapport, which makes them believable sisters, and they play moments of discomfort, fear, and sadness authentically. With these excellent performers anchoring Seagrass, the film delves into specific aspects of Japanese-Canadian generational trauma.

Judith’s immigrant parents’ lives of hardship, which included internment camps and poverty, places guilt upon her as an adult and forms a cultural barrier between her and her white, affluent husband. The demands of familial duty are passed on from Judith to Stephanie, who is given the responsibility of watching over Emmy throughout the vacation, but Judith’s harsh criticisms slowly build up resentment between mother and eldest daughter. Small conflicts eat away at the family’s stability, and each character is too caught up with their own problems to fully realize the impact their emotions are having on their loved ones until it’s too late.

There is a deliberate uneasiness brought about by the visuals and score in Seagrass. The film boasts stunning shots of the Pacific Ocean’s unrelenting tides, terrifying black cliffs, and lush seaside plant life that make the British Columbian setting absolutely striking. Waves crashing and wind whooshing fills the eyes and ears between scenes, feeling otherworldly and mysterious. The camera also holds on certain scenes, charging them with tension, or hovers eerily over characters, swaying and floating like an unmoored boat. A constant low level of discomfort leaves viewers wondering where things will go in the family drama, whether Seagrass will actually cross the line into a true horror. This proves to be critical upon the film’s climactic end, when viewers are left to fear that the worst has happened.

Subconsciously, these elements create a sense that metaphorical ghosts haunt Judith and her family. The conflicted matriarch reckons with generational trauma and guilt as someone who is aware that her parents were hard-working immigrants who had suffered the indignities of Japanese internment camps but never spoke about their experience. Judith, too, lacks the words to vocalize why she is unhappy, why her marriage feels wrong, and why her mother’s death has impacted her. She can’t even explain to her husband why one of his comments about Pat were racist or why her daughter shouldn’t pull her eyes into slants and parrot, “I’m Japanese,” like some white boys had been doing. Only when she gives herself enough time to think and see alternate life paths than the ones laid out by her parents does Judith begin to find her answers, and hopefully, break the cycle of silence and trauma for her daughters.