The biggest news of this year’s Cannes Film Festival is the dramatic late addition of Mohammad Rasoulof’s film in Competition, as the dissident Iranian filmmaker faces an eight-year prison sentence for filmmaking and has fled his home country to Germany as a political refugee. The Seed of the Sacred Fig doesn’t even need to be good to win sympathy points, but that it’s a soaring masterpiece confirms Rasoulof as one of the bravest and most brilliant filmmakers working today.

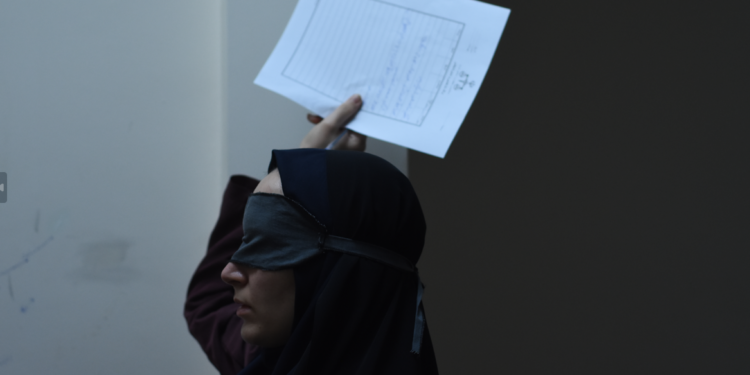

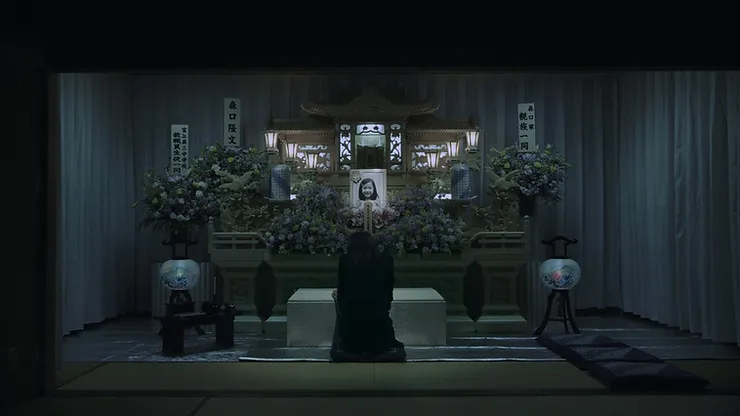

More than just “set against the backdrop” of the 2022 Mahsa Amini protests, Rasoulof’s drama explicitly confronts the protests that rocked Iran. We begin with protagonist Iman (Missagh Zareh) who has won a hard-fought promotion to the position of investigating judge in the Iranian courts. Given a gun to protect himself in this sensitive role, he is an upstanding civil servant who tries to resist the unjust prosecutorial orders of his superiors. At home are the matriarch Najmeh (Soheila Golestani) and his two daughters Rezvan (Mahsa Rostami) and Sana (Setareh Maleki). As the parents instruct the children to live low-key and spotless lives because of father’s promotion, the protests begin, and the direct participation of Rezvan and her best friend Sadaf (Niousha Akhshi) bring the bloody protests home. Political conflicts within the family emerge, and just at this critical moment, Iman loses his gun, launching him into a frenetic conspiracy against his own family.

The first thing that must be praised is the incredibly courageous context of making the film. This isn’t to give brownie points to the whole cast and crew; the context is part of the film’s text itself. Rasoulof would’ve received praise just for hinting at the protests, but that he has incorporated real-life vertical videos of the events into his film makes The Seed of the Sacred Fig radically polemical. The approach is similar to Spike Lee’s in Malcolm X and BlacKkKlansman, and while some critics will certainly cry for more subtlety and less “didacticism,” is there really room for distance when the situation is so dire and urgent? Rasoulof has wisely chosen to let the footage speak for itself.

And it’s not just the little vertical clips that elevate the film. Through dialogue, Rasoulof has very accurately captured a family in reasonable political strife. The points they make directly address the protests, and one gets the feeling that everyone involved in writing, speaking, and capturing these lines is doing something transgressive, illegal, and incredibly courageous. It has never been possible to remove filmmaking from context, and it’s these real-life circumstances thrumming underneath every line that make Rasoulof’s film so stirring and powerful. When watching this film, we know we are witnessing activism in real time.

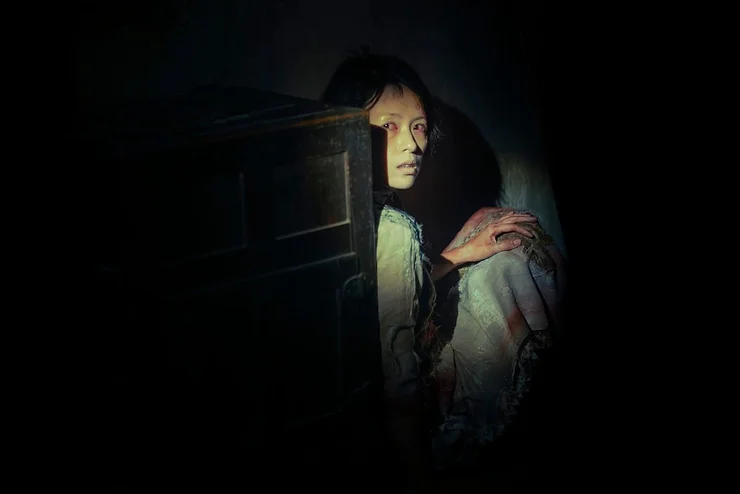

It isn’t just the context that solidifies the film; the dramaturgy is brilliant as well. When blood has been shed and torture has been used halfway through the film, the Hollywood directive would be to keep escalating the film’s stakes and making it bigger. But perhaps Rasoulof knows within his limited resources that he can’t top the footage of the large-scale demonstrations, hence his ingenious decision to downsize the conflict and bring it back to the family unit. By doing so, he makes the entire nation’s divide intimate and personal. The escalation of the film will certainly remind people of fellow Iranian Asghar Farhadi’s snowballing dramas, yet Farhadi’s stakes always feel artificial and manipulative. In The Seed of the Sacred Fig, even when characters make nonsensical decisions, they serve a more illuminating, greater point, and the second half’s genre-flavored implosion only feels like a logical conclusion to the state’s iron-fisted patriarchy.

Again, with the superb writing, Rasoulof’s film only needs to be formally functional to be good. But there are also moments of formal ingenuity. An early shower transforms into a cleansing of the soul, and the handheld long takes towards the end heighten the paranoia in the tradition of classic thrillers. Let’s not forget that for this film to work, the drama needs to have utmost authenticity, and Rasoulof has certainly gotten it out of his cast. Even when he is only doing filmmaking 101 essentials like shot-reverse shot, it is seamlessly directed and edited, and that classicism only makes the real-life vertical videos jump out more.

As a writer from Hong Kong, I admit I may be biased. The Iranian protests situation is similar to Hong Kong’s, only a lot worse. That Rasoulof has been able to make this film merely two years after the protests is simply astonishing, and he has sadly, predictably, risked his life and safety to do so. He claims he shot this film invisibly and only had a small crew and no professional equipment, which is unbelievable, since there are car chases and foot chases depicted (and the film looks very professionally lit as well). Everything he’s done only makes this more of an accomplishment, and even though the filmmaking context is so inseparable from the film, the 168-minute drama is a stirring masterpiece of its own. Greta Gerwig’s jury may have given this a rather insulting “Special Prize,” but there is no better film at this year’s Cannes Film Festival.