“Whenever I start creating something from the blank paper, women characters always come to my mind first,” Park Chan-wook says via an interpreter, as he sits forward on a non-descript grey couch in a Toronto hotel room.

He continues in a soft-spoken, measured tone, contrasting the somewhat frenetic pace of his films, “I feel that in the television and film world, there’s still more room for women characters to really stand out. And there are so many diverse things that we can explore about [them].”

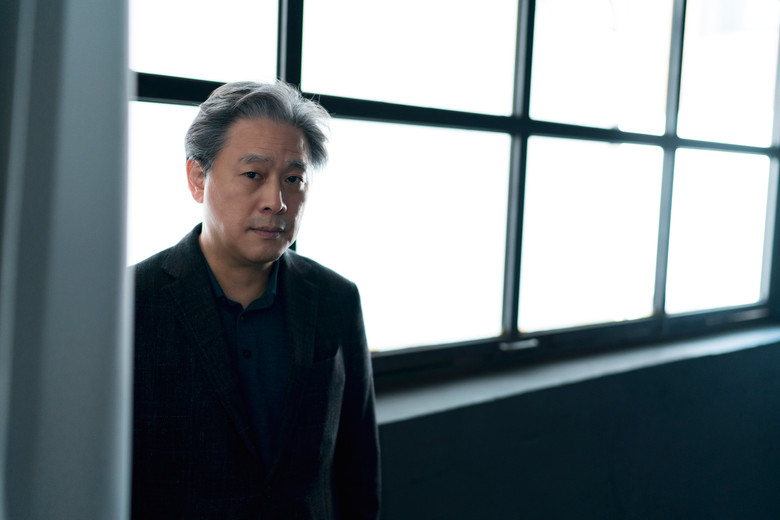

Along with five other journalists, I sit across from the illustrious director in a hotel suite during the 2022 Toronto International Film Festival, a couple days ahead of the North American premiere of his new film, Decision to Leave. A mix of recorders and mobile phones are piled up in front of director Park as he thoughtfully considers each of our questions before offering astute observations and opinions that pull back the curtain ever so slightly on his process.

Like so many others, I was introduced to director Park’s work through his action thriller Oldboy. Now considered a modern classic, along with Kwak Jae-yong’s My Sassy Girl, Oldboy ushered in our current era where South Korean entertainment reigns supreme throughout the world. To Park, though, this boom is simply the result of a maturation process that saw the end of censorship after a long period of political instability, an influx of investment into the country, and the advancement of film technology in South Korea.

“These three elements are the basic foundation for anything to flourish,” Park patiently explains. There’s a degree of excitement in Park’s voice when discussing his country’s progression in the film industry that speaks to his passion as a filmmaker and his national pride: “I think that during the 2000s, Korean films really started to tap into those [elements], and since then, Korean soil has been very mature, and we are reaping those fruits now.”

There’s no doubt that Oldboy has cemented its place in Korean cinematic history, but what has always intrigued me about director Park is the film that came after. Lady Vengeance is the final film of Park’s aptly titled, “Vengeance Trilogy,” along with Oldboy and Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance. It’s the only film in the trilogy to have a female protagonist and would signal the beginning of Park’s exploration of the female psyche that came to a head in the BBC series The Little Drummer Girl and the magnetically absorbing film, The Handmaiden.

This seemingly sudden pivot in Park’s career, like every detail in his films, was entirely intentional. Park grappled with the fact that Mi-do, the lone female lead character in Oldboy, was the only one not to know the truth by the end. Granted, this decision was purely driven by the story’s narrative, but Park felt bad for her because, “as a creator, your characters become your own.”

And so, Park resolved to recognize this new awareness he had in his storytelling. “I tried to put the female characters more at the forefront,” Park tells us. “[I wanted to] give her a more active role in driving the narrative forward. Give her more power, if not the same power, as male characters in the story.”

“After Oldboy, I tried to find a female co-writer to work with. I found Chung Seo-kyung and that’s where that journey began,” continues Park. “[Chung] is one of my best friends and we’ve written many different films [together] for a very long time now.”

Their latest collaboration, Decision to Leave, is a thrilling mystery that emphasizes the highs and lows of obsession, desire, and deceit. The film has a neo-noir texture but Park is careful not to categorize his work in any particular genre lest he be forced to follow a particular set of associated conventions.

“I [thought] that this story should have one axis where the audience will follow the process of one detective encountering a case and trying to solve that case. And at the same time, the other axis is the love story,” Park recalls in a calm, rhythmic cadence. “From the very beginning, we [Chung and I] had a big objective of making the process of investigation and making the process of these two characters falling in love [and] becoming completely inseparable, completely amalgamated.”

Park may rebuff the film noir tag — “looks like noir, but not quite,” he says with a diverting chuckle — but the lead female character in Decision to Leave has the strong impression of a femme fatale. Played by the eminent Chinese actress Tang Wei, Seo-rae is the mysterious widow whose husband has fallen to his death at the beginning of the film.

Detective Hae-jun (Park Hae-il) is tasked with solving the murder but finds himself helplessly captivated by Seo-rae. Her confident gaze becomes muddled in a soft vulnerability combined with an overwhelming, yet somehow subtle, sensuality that intoxicates the detective. Seo-rae is not all that she appears and by the end of the film, the audience and Hae-jun are left with a puzzle of missing pieces.

The journey that Park says began when he started writing with Chung on Lady Vengeance comes full circle with Decision to Leave. Going from Mi-do, a young girl who is the victim of circumstances created by men, to Seo-rae, a woman who deftly dictates her present and future, shows the growth of a filmmaker and a man. With the help of Chung, Park has methodically and earnestly analyzed the nuances and intricacies of the female soul and spirit over the last two decades.

“There’s something very amusing about how we work together,” Park shares. “Usually, whenever we’re writing a woman character, I try to make her as cool, chic, and smart as possible. She [Chung] always tries to give something faulty to the character or tries to make her a little bit unethical. And it’s the opposite situation when we are writing a male character.”

As our time with director Park runs down and we say our good-byes, I’m struck by the ease and matter-of-fact nature he discussed a topic so potentially fraught with click-bait landmines and PR nightmares. His assured poise could be due to a number of reasons, but his comfort with the subject after having so meticulously dissected it certainly plays a factor.

Therein lies the key to what makes Park’s work so arresting and gripping. It isn’t the swish camera movements or rich soundscapes that he creates (although they don’t hurt); it’s his fastidious examination of the human condition, driven by a genuine curiosity to understand the world around him that he so effortlessly presents to his audience.