Time in film is rife for artistic flare, a veritable playground for creators to fill with or empty of story and action. It can drag along, weighty as brick through sludge, with lush or sparse action stretching the expanse of a short period, so that an entire life seems to be lived within what ends up being mere minutes. Or it can be spitfire, with numerous days and hours, characters’ ages and entire lives, rushing before us at breakneck speed, whipping us into a frenzy. Time’s length within a particular film depends on the mood and intentions of the film and its creators. But what remains relatively straightforward in most mainstream films is that time functions as a space or dimension to be filled; it’s a setting whose demeanor is often determined by a narrative’s affect.

In Wong Kar-Wai’s In the Mood for Love, time weeps — functions as subjective memory in action. It rushes by when things are apparently good, so as to all the sooner arrive at the blissful moments, whereupon it lingers and snags. When things become painful, time lingers and snags, too, as if stunned by the hurt. At first sight, there seems to be no rhyme or reason behind the cadence of time’s step in this film. But surface-level readings never did us much good.

Actually, time in In the Mood for Love carries an urgency that feels pregnant, an intentionality that is unignorable. Time in this film seems a palpable, fallible character unto itself, a freighted lens like a first-person gaze or a directed reminiscence. This film seems as if related by time, an invisible but deeply subjective, oftentimes obfuscatory, player in this tragedy of love. It allows for Wong to depict the frustrated love at the film’s core with a disorienting and confounding heft and resonance; with an immediacy we, as viewers, feel as a knife lodged within our side, as though the plot were happening to us, too.

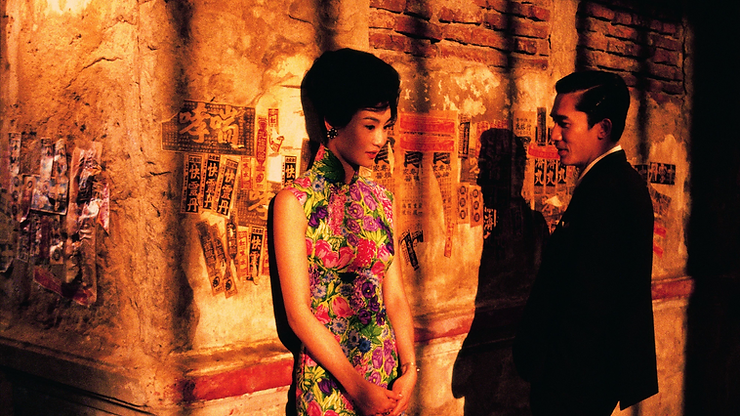

The story (penned by Wong) follows neighbours Mrs. Chan (Maggie Cheung) and Mr. Chow (Tony Leung), who discover that their spouses are cheating on them. Heartbroken, the two seek counsel and solace within each other, often acting out possible scenarios so as to better understand what brought their spouses to cheat, so as to better understand their heartbreak. The two decide to keep things platonic, but, inevitably, as the two form a deep and visceral bond based on mutual respect and creative passion (not merely for crafting scenes of infidelity, but also of actual fiction writing — Mrs. Chan helps Mr. Chow write serials, fulfilling a frustrated childhood dream), they fall irrevocably and monumentally in love.

The first 15 minutes of the film are expository, containing a whirlwind. A plethora of events transpire and commingle over the filmic space of a short period of time. The Chans and the Chows move into neighbouring rooms. We learn of Mrs. Chan’s husband, her job, her boss; we learn of Mr. Chow’s work, his deflated dreams, his love for his wife, and his sleazy friend. We watch as the two settle into life in their new homes, settle into the rhythm of domesticity, of waiting for their spouses to come back from work, from work trips. We learn, ultimately, of each Mrs. Chan’s and Mr. Chow’s love for their spouses.

What is also revealed through breaks in ostensible bliss is the start of the affair between Mrs. Chan’s and Mr. Chow’s husband and wife, respectively. Often, love stories chart a love blooming slowly at first, and then all at once. Here, however, the affair takes place all at once, and then Mrs. Chan and Mr. Chow’s love blooms slowly, as they work together to regain a sense of control with the miasma of grief and confusion. Their love crucially never seems to reach a cataclysmic fruition.

The quick pace of the first chapter of the film has the effect of leaving us with whiplash, as tragedy is often wont to do. The affair erupts, and Mrs. Chan and Mr. Chow, in pain, are left to pick up the pieces, slowly. Wong’s timing here seems sympathetic and kind, employing a gaze that, though it registers, doesn’t linger on the painful aspects for too long. Similar to the way in which we might, in remembrance, wince as we flick through the broad strokes of the ugliness we experienced, not forgetting it altogether, but also not belabouring the razor-sharp point, so as to all the sooner arrive at the work required to rebuild.

Wong’s lens lingers over Mrs. Chan and Mr. Chow as they spend time together, walking, sitting in silence, sharing meals, talking through their thoughts, role-playing. The time the two spend together is all they have, and it would be what a memory would also choose to remain within — relishing those sensations of time spent eating, laughing, exchanging ideas, moments of weeping on each other’s shoulders, moments of consolation. These are sweet moments, like the one innocent night the two spend in Mr. Chow’s bedroom, confined there after an afternoon spent writing by their landlords who return home earlier than expected — at one point a drowsy Mrs. Chan watches a sleeping Mr. Chow, simply studying him.

These are the kind of moments that we look back on after much time has passed and that taste like sugar and feel like home. These are the moments we want to remember when we have nothing else left.

This is the tenor of Wong’s time. What it seems to communicate — a desire to cherish the good and the mundanity, or pragmatic texture — it contains. When time does linger in pain, such as the phone call Mrs. Chan makes to Mr. Chow long after they have parted ways, during which she weeps without saying a word, time’s focus seems to be on love’s effort and its practical ineffectiveness. A kind of frustration we often massage in remembrance because it feels good in the way pressing on a bruise feels good. Lingering in the good includes treasuring the pains love contains, pains that love makes sweet, for they allow us to exalt and deify frustrated love.

As the film unfurls in its clipping way, time starts to slow, often trapping the characters within it in deft and mesmerizing freeze frames. It’s a savouring of the complicated good, the slowed time, Wong seems to show. It’s apparently an effort to hold past action, and its attendant intentions however misplaced or foiled, as a photograph and to admire it. Matters become less and less about a desire to overcome the pain of infidelity for the two, and more and more about a desire to spend time together — to remain suspended in the amber of perfect love.

They step away at the right moment, before everything is destroyed. As the frames bask in the pain the two suffer in separation, what is also being cherished is the untenable, platonic ideal of love they created between them, which makes the heartbreak all the more deliciously painful. It’s a love too good for the earthly realm.

Because of Mrs. Chan’s and Mr. Chow’s almost obsessive and masochistic desire to understand their cheating spouses through roleplay, we are often thrust into scenes without being entirely certain as to whether the exchange unfolding between Mrs. Chan and Mr. Chow is their own, or a projected, anguish-inflected recreation of what they believed to have transpired between their spouses. This, too, seems to be one of time’s tricks, part of the act of remembering the good, for these moments of roleplay are almost like sex for the two. Delicious and addictive and soothing.

Less and less the roleplaying seems to be about their spouses, and more about a way to communicate something incommunicable that is their own to each other. Later in the film, the roleplaying seems to be an abeyance of parting, sweet and feebly-concealed excuses to stay together for a while longer.

As the diegetic time lapses, Wong’s time hastens, in the way that psychic pain lessens with distance, and only in surreptitious gasps is the love that each feels for the other allowed to burst to the surface. Mrs. Chan and Mr. Chow move about each other, chasing the feeling they once had, that Wong’s time as memory charted, but they are too afraid to go back into the past, to truly and meaningfully touch.

As the film nears its conclusion, time lapses quickly again. The quick pace of the final act of the film is like time’s final grace. With In the Mood for Love, Wong, as he depicts one of the most heartbreaking love stories ever told, manages to paint it in the tenderest, most gentle way, with an immense love for his own protagonists, all through the figure of time that feels like a kind friend, or a memory whose active work is informed by the knowledge that love has left us forever fragile. In the Mood for Love does a great justice to its title, offering glimmering beauty and happiness for when we are in the mood to spend some time in sweet, sweet tenderness and light.