It has long been tradition for outspoken Chinese filmmakers to present their films as foreign productions to get around the ever-changing, arbitrary, and iron-fisted censorship guidelines of the Chinese government’s National Radio and Television Administration. Like many other things in China, this practice has been rather cracked down in the last ten years.

But after battling Chinese censors and suffering delayed, hampered releases of his last two narrative films, The Shadow Play and Saturday Fiction, sixth-generation arthouse icon Lou Ye has made a splashing return to the Cannes Film Festival with An Unfinished Film, officially a German-Singaporean co-production. His docufiction hybrid film has been relegated to an unglamourous “special screenings” spot, but it is one of the most fascinating films of the entire Festival so far.

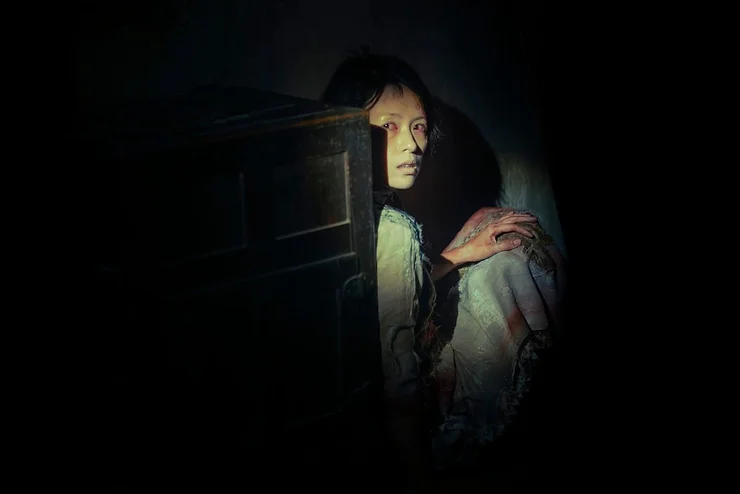

An Unfinished Film is a behind-the-scenes “documentary” of a film production crew, led by director Xiaorui (Mao Xiaorui), attempting to finish a project they started shooting ten years ago. The project appears to be a sequel to Lou’s own gay Chinese classic Spring Fever, which actually competed for the Palme d’Or in 2008. Xiaorui has secured the reluctant participation of lead actor Jiang Cheng (Qin Hao) – Jiang Cheng being the name of Qin’s character in Spring Fever. Production finally begins after a ten-year-long hiatus, but unfortunately everything gets shut down in an instant when the coronavirus lockdown in Wuhan begins. The authorities lock the entire film crew in separate hotel rooms, as the crew figures out their next steps.

Immediately, the above premise may confuse you. Who is Xiaorui? Didn’t Lou himself direct Spring Fever? Was there ever a proposed sequel to Spring Fever? Why is the prolific Qin Hao calling himself Jiang Cheng in this “documentary”? All this means the central, most intriguing question of the film is: how much of the film is real, and how much of it is staged? Stylistically, Lou presents An Unfinished Film as a harrowingly realistic and convincing documentary, with the notable exception of a camera crew that couldn’t have possibly existed in quarantine. (Or maybe it could have? We are shown the backs of some cameramen.) Lou fluidly and playfully toys with the line between documentary and fiction, using every tool at his disposal, including his signature handheld camera to make us believe the reality of what he’s trying to say.

The film can be broadly broken down into two halves, the first half being pre-lockdown. An Unfinished Film starts in 2019, when Xiaorui fixes a decade-old Mac Pro to review the “Spring Fever 2” footage. Through knowing glances and hinted conversations, the crew acknowledges what kind of film they’re making. In 2008, China was at its most liberal, and lots of things have regressed even further since. Even then, Spring Fever was an entirely underground, unapproved production and officially a French film. The explicit gay kisses and fondling in Spring Fever 2 cannot possibly be released or even made nowadays. When Xiaorui officially invites Jiang Cheng to rejoin the cast, the actor explicitly states, “Your film will never pass censorship.” Yet what does Jiang Cheng do? He shows up on set anyway.

The first half of An Unfinished Film is an incredibly moving and invigorating ode to the courage and tenacity of independent artists, risking their careers and even reputations, safety, and families for so little. They know what they’re doing is at least transgressive if not illegal, but they still do it. Lou shows that even in Xi-era China, a fighting spirit is alive.

The second half of the documentary moves to the lockdown, and while it is certainly still compelling, it lacks the specialness of the first half’s filmmaking angle. Since the pandemic, there have been so many COVID documentaries made, like 76 Days and In the Same Breath, and as grippingly — and even violently — as Lou portrays the initial outbreak of events, An Unfinished Film eventually becomes just another COVID documentary about people in lockdown.

Even though there is pointed anger and frustration towards the Chinese government’s untransparent and unreasonable policies, the film’s ode to the survival and spirit of the people even becomes quite “main melody”-like. Shockingly, Lou even abandons his famously highbrow aesthetic sensibilities to include Douyin (Chinese TikTok) vertical videos and children’s covers of songs that went viral on the Chinese internet. There’s nothing necessarily wrong with these things, as they still move and stir the heart, but anyone could’ve made this portion of the film. Only Lou could’ve made the first half.

Before the Cannes Film Festival even began, the horrid political prosecution and subsequent escape of Iranian filmmaker Mohammed Rasoulof had been dominating conversations and headlines. Rasoulof’s situation obviously needs to be talked about, but let’s not forget the incredible tenacity of artists like Lou (and his crew of unfamous, ordinary citizens who appear in the film) as well. Lou has gotten into so much trouble and filmmaking bans in the past, but after yielding to the State for his last two films, he’s still back as a “bad boy.” By sending this film to Cannes as a foreign co-production, Lou has bypassed the Chinese censors and the required “Dragon Emblem” to show the film, almost certainly angering the Administration again.

That An Unfinished Film is directly about this — a rebellious group of filmmakers shooting an even gayer sequel to Lou’s own illegal film — is what makes it so powerful and stunning. Combine that with the docufiction experimentation and the overflowing earnestness and authenticity of the film, and we have one of the under-sung yet undeniable triumphs of the Festival so far.