All the buzz surrounding Payal Kapadia’s film All We Imagine as Light is that it is the first Indian film in 30 years to be selected by the Cannes Film Festival in the most prestigious Competition section. That is, of course, a massive disservice, and an unfair pressure to place on the young Kapadia’s sophomore effort. Yet, her beautiful film has weathered these expectations with ease, deservedly taking home the Grand Prix of this year’s Competition. Even though there is still room for refinement, there is no denying Kapadia is bursting with talent.

Set in Mumbai, All We Imagine as Light tracks the lives of three women who have moved from rural villages to work as nurses in the big city. The lead is Prabha (Kani Kusruti), whose husband from an arranged marriage now works in Germany, not having seen each other in a long time. On the contrary is her younger roommate Anu (Divya Prabha), who is defying her parents’ and society’s wishes by dating her Muslim boyfriend Shiaz (Hridhu Haroon) in secret. In her spare time, Prabha helps the elderly, undocumented Parvaty (Chhaya Kadam), who is facing eviction from a gentrification project. The lives of these women intersect as they take on these conflicts.

The above synopsis certainly has the potential for a dramatic soap opera. Kapadia tackles big, hot-button topics of contemporary Indian society almost like they’re off a checklist: Hindu-Muslim relations, arranged marriage, gentrification, the city vs. village divide, etc. Yet she resists the temptation to push those buttons and turn her film into an actual soap opera. Kapadia has no interest in the traditional Hollywood methods of raising stakes and conflict resolution; she knows that her film alone cannot resolve Hindu-Muslim tensions. Instead, she gears her film towards finding solidarity and peacefulness. Where filmmaking norms suggest she should escalate and go bigger, she recedes into beautiful, common solace.

The ambition of the film means it can sometimes feel all over the place. Parvaty’s storyline fighting for her rights certainly feels like an afterthought. A random leftist union scene appears once and is never addressed again. The first act is worryingly weak — after a pretty voice-memos montage that starts the film off, it meanders around for a good 20-30 minutes before firmly establishing the premise. The stylistic influences are varied, too: the city poetry of Mumbai in the first half is akin to Wong Kar-wai’s Hong Kong, Lost in Translation’s Tokyo, and Her’s Shanghai. She successfully conveys the varying vibe and vibrancy of the world’s sixth-most populous city. It has the mark of a young lens too, with text messages prominently plastered across the screen.

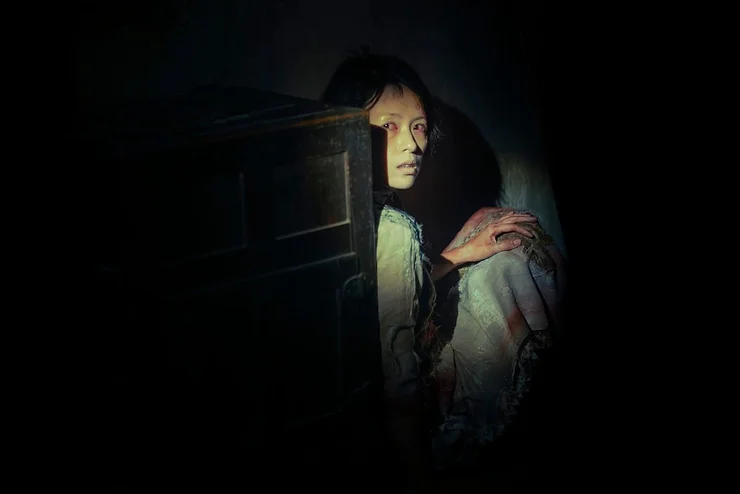

Yet the second half transforms into the slow-cinema mysticism and even magical realism of Apichatpong Weerasethakul, and the two halves don’t gel well. It can feel like Kapadia is trying to tackle too many styles at once. In the name of naturalism, many shots are downright underexposed, and even though one can tell she has great talent and taste, her style needs further refinement to be truly her own.

Still, for a sophomore feature, this is quite the announcement to the stage of international cinema. Cannes took a big risk on young talent, and it paid off. The tenacity of the filmmakers shouldn’t go unmentioned either. All We Imagine as Light starts with the names of literal dozens of worldwide funding bodies, a testament to how difficult it is to make an indie film like this in India. It is even sensually sex-positive feminist, raging against taboo in Indian society (the many critical themes will make a theatrical release unlikely in the film’s home market).

But we aren’t just rewarding Kapadia for the effort. She has intimately captured the strong, complex bond between women of multiple generations, avoiding all the traps of didacticism. In themes, narrative, and style, her film can feel too ambitious and greedy, but that is both the inexperience and, more importantly, hunger of a young filmmaker. As successful as this film already is, it is probably not her masterpiece yet. It may very well be a minor work by a major filmmaker to come.